The Effects of Verbal Affirmations on Student Motivation in the US History Classroom

Abstract

The present study uses a mixed methods approach to analyze the effect of two types of verbal affirmations of high expectations on student motivation in the context of three sections of a high school history class (n= 54). This year, students in a small, career and college-focused, urban charter school in Indianapolis, Indiana have demonstrated low academic motivation as evidenced by low assignment turn-in rates, leading to lower GPAs and a higher number of failing classes. The objective of this study is to interrupt this pattern of low motivation through a non-content specific teacher intervention, after which student motivation is observed using a questionnaire with both qualitative and quantitative data points. The results demonstrate that some students do perceive verbal affirmations of high expectations as motivational, but at a much lower rate than other strategies used by classroom teachers. Instructional and classroom management strategies, intrinsic interest in the subject and quality home practices were reported as the primary factors affecting student motivation across the intervention. Data suggests that classroom teachers should focus on developing their pedagogy to (a) promote student interest in their respective subjects and (b) to create an educational environment in which students feel supported academically by way of adequate learning conditions and sound teacher scaffolding.

Keywords: student motivation, secondary history, affirmations

Introduction

Student motivation is one of the most important factors influencing the field of education, as it directly impacts the way students participate in the classroom. Being motivated can positively impact a students ability to set goals, develop talents, and other skill sets beyond academic achievement. However, student motivation can be difficult to measure and even harder to directly improve through intervention, with some interventions yielding little to no improvement in student motivation levels (Sibieta, Greaves & Sianesi, 2014). Many teacher interventions have been attempted across multiple contexts and with varying success, from content-specific instructional strategies to more general classroom management strategies (Seifert, 2004; Yilmaz, Şahin & Turgut, 2017). While research is ongoing, there is still much to be said about what affects student motivation and what the teacher’s role in promoting it is. This conflict has become more apparent in my own teaching career as low motivation is negatively impacting the students I teach. If left unregulated, chronic low motivation during a student’s K-12 education could severely limit one’s trajectory of life.

In my current context, students at a small, career and college-focused, urban charter school in Indianapolis, Indiana are experiencing low motivation in class, often resulting in very low assignment turn-in rates. This leads to a higher number of failing classes and low GPAs across all grade levels. Data from this school year shows our schoolwide GPA was a 2.49 in Semester 1, which is significantly lower than the previous four years. From August to January, 341 total courses (including dual enrollment courses) were failed. This data indicates that, on average, students at this school perform between a C and B average, with roughly one F on their transcript each semester. In my AP Psychology class, 17/38 students had more than two missing assignments out of seven for the month of January. This demonstrates that this issue is even prevalent in our most rigorous courses, with our most academically prepared students.

Conversations with students revealed academic burnout as the issue. Many students have household responsibilities that compete with their schoolwork, from caring for siblings while parents are at work, to working their own job to help support their family. This two-factor workload requires above average focus and discipline, which only a few are able to master at a young age. This predicament contributes to a severe lack of motivation amongst a large portion of the student population, consistently resulting in: students giving up before completing relatively rigorous assignments, failing to follow through on academic commitments outside of school, and having apathetic views toward school in general.

Given the overwhelming correlation between student motivation and academic performance, it is essential that educators assess their roles in promoting student motivation. To explore potential solutions for classroom teachers, this study examines a teacher’s use of two types of verbal expressions of high expectations in an attempt to increase student motivation. Two types of verbal expressions are delivered to account for different teaching styles. While the unique types of verbal expressions of high expectations yielded varied results, the data suggests that classroom management and instructional strategies are the most reliable pedagogical predictors of student motivation in the classroom. The implementation process also provides nuanced insights into how teachers can assess student motivation with increased validity.

Literature Review

For decades, educators have witnessed that when students experience low motivation in school, there are drastic effects on their academic performance. Beginning primarily in the 1980’s, educators have researched student motivation by focusing on two questions: What factors affect student motivation, and what is the effect of student motivation on academic performance? The literature has consistently demonstrated there to be a positive correlation between the two variables, across multiple contexts (Lumsden 1994; Bernaus & Gardner, 2008). For example, although there were “a complex of factors” motivating these two variables, researchers in an English as a Second-Language (ESL) classroom context found a positive correlation between student motivation and “L2 achievement,” or second-language mastery (Bernaus & Gardner, 2008). These findings implicated the importance of student motivation in promoting student success, which then shifted the research towards identifying those specific factors that impact student motivation levels.

Research into the factors that are correlated with student motivation resulted in the identification of numerous external (environmental) and internal (psychological) factors that support, or suppress, student motivation. Existing research has described student motivation as a “competence” that is affected by myriad things, from home environment and teacher perception of students (Seifert, 2004), to specific instructional and classroom management skills employed by teachers (Yilmaz, Şahin & Turgut, 2017). A teacher’s influence on student motivation is multivariate and can even be the product of implicit teacher behaviors. For instance, Linda Lumsden mentions that teachers’ perceptions of their own profession will even influence the expectations they set for their students, ultimately impacting the way students are motivated to learn (Lumsden, 1994).

Despite the role of implicit behaviors, researchers are much more focused on explicit actions a teacher can implement to impact student motivation. In the same study, Lumsden attempted to improve student motivation using “attribution retraining,” a cognitive approach that helps students eliminate the barriers of low-self worth and fear-of-failure (Lumsden, 1994). McMillan and Hearn identified a four-step process through which teachers can help facilitate student self-assessment over numerous class periods, an instructional approach that ultimately helps students build academic motivation and confidence (McMillan & Hearn, 2008). Lastly, a comprehensive literature review demonstrated the connection between classroom management strategies and student motivation through prior research (Yilmaz, Şahin & Turgut, 2017). Each study is a clear indication that teachers have an effect on student motivation, and there are plenty of opportunities for teachers to be intentional about the strategies they use to directly motivate students, or to at least facilitate an environment that is conducive to motivation.

A gap that exists within the literature on student motivation is that most teacher interventions limit their independent variables to content-specific instructional strategies. For example, Bernaus and Gardner’s motivational strategies were instructional strategies in an ESL course, and could only be implemented in that specific context (Bernaus & Gardner, 2008). Similarly, McMillan and Hearn’s intervention strategies were based in metacognitive self-assessment strategies and would only be implemented in tandem with a larger assignment that has multiple components (McMillan & Hearn, 2008). However, there are very few studies strictly predicated on non-content based strategies that teachers from multiple disciplines and grade levels can also adapt to their classroom environment.

Certain studies on student motivation were closely aligned to the professed goal of this research study, and offered valuable insight into methodology and data collection practices that ended up assisting in the research design and data collection for this study. For example, the use of self-assessment surveys formed the basis of the data collection for this study (McMillan & Hearn, 2008). Similarly, the importance of student perception of interventions demonstrated by Bernaus and Gardner inspired question number three on the questionnaire (see methodology), which was included to assess whether students perceive the intervention as motivational (Bernaus & Gardner, 2008).

Methodology

Research Design

The study applies a mixed method approach to assess the impact of verbal affirmations of high expectations on student motivation. The research used a questionnaire to gather both qualitative and quantitative data from US History students about their motivation levels in class and their perception of the teacher's intervention strategies. The questionnaire consisted of five questions (* = responses provided quantitative data):

On a scale from 1-5, how motivated were you throughout today's USH lesson?*

Explain your rating. What contributed to your motivation (or lack of motivation) today?

From your perspective, did Mr. Bolden use a motivational strategy today?*

Explain your last answer. What does Mr. Bolden do (or not do) to motivate students?

(Optional): What could Mr. Bolden do better to motivate students in his class?

The five questions were formulated to provide insight into the following research questions:

How will teacher-led verbal affirmations of high expectations in class affect student motivation (question 1)?

Did students perceive verbal affirmations as an intentional motivational strategy (question 3)?

What other factors may influence students' motivation outside of teacher intervention (question 2)?

What other teacher strategies do students perceive as motivating (question 4)?

Questionnaires allow for both qualitative and quantitative data collection, which is key to understanding student perceptions of teacher intervention (Bernaus & Gardner, 2008). Since the intervention in this study is a general SEL-based practice that was not explicitly named or taught in the US History class, measuring student perception of the intervention is important to understanding the relationship between the independent variable (teacher intervention) and the dependent variable (student motivation ratings). The qualitative data will provide context to both quantitative ratings by eliciting verbal explanations to the quantitative data gathered in the questionnaire.

The class is taught in cyclical two-day units, with parallel lessons (same structures, different primary source and comprehension questions) being administered on every two days. The teacher intervention and questionnaire were consistently administered on day one of the two-day lesson cycle, which consisted of individual reading time and comprehension-based group work.

Participants

The study is being conducted in three separate sections of a general 10th grade US History class at an urban, public college and career preparatory charter school in Indianapolis, Indiana. The school consists of 332 students, with 99% identifying as Black or Hispanic and 95% qualifying for free or reduced lunch. There are 55 students across the three sections: 48 sophomores, 6 juniors and 1 senior (the upperclassmen are taking the class for credit recovery). There are 33 male students and 22 female students; 14 have an IEP and 12 are second-language learners of various WIDA scores.

Intervention

There were two types of verbal affirmations administered in the US History class, one per week of data collection. During week one of data collection, the verbal affirmation was said once, out-loud to the entire class, at the beginning of comprehension-based group work time (at this point in the lesson, students have already researched the topic of the day and have silently read our primary source). The affirmation read, “I expect all students to fully complete today’s assignment. You may productively struggle, and that’s good. I know you are all capable of finishing and producing quality work.” During week two, the verbal affirmation was delivered at the same point in the lesson. Instead of repeating the affirmation once for the entire class, the affirmation was first initiated by the teacher and then repeated by the entire class, sentence by sentence. The affirmation read, “I will productively struggle. I will work through the challenges and give my best effort. I know I am capable of producing quality work.” After the verbal affirmation was administered, students were then given time to complete their group work until there were five minutes left in class. At that time, the entire class would transition to the motivation questionnaire, where they would respond to the questions on their own before departing to their next class.

Data Analysis & Fidelity

The data analysis process requires two steps. The first step is to assess the relationship between the type of teacher intervention and student perception and student motivation ratings. This consists of calculating the average motivation ratings from each week and comparing results based on the type of affirmation provided; teacher-led or repetition-based. This step will also include using pattern identification to search for themes across the qualitative data, providing insight to what specific factors motivated students during data collection and what teaching strategies they perceived as motivational throughout the lesson. The second step is to assess the relationship between student motivation and student academic performance. This consists of totaling the number of missing assignments per week and comparing the results based on the type of intervention provided each week. These two steps align with the hypothesis, assuming there to be a positive correlation between the interactivity of teacher verbal affirmations and student motivation. Since we have already established a positive correlation between student motivation and academic performance, the second step allows us to compare established research findings to current results within this specific context.

Several measures were taken to account for research fidelity within the research design and data analysis process. Using the questionnaire to gather data about student perception of the intervention promotes validity by providing context to the relationship between the independent and dependent variables (students being unaware of the motivational strategy could yield different results than if students knew they were being motivated but the strategy was simply ineffective). Since the questionnaire was administered after very similar lessons within the two-day lesson cycle (the only difference between the four lessons were the specific primary source being analyzed), confounding factors that could have emerged from students completing the questionnaire after engaging with various types of lessons and activities were ultimately prevented. The student responses were also collected anonymously, giving students more freedom within the process which ultimately allows for more honest responses. Similarly, students had at least five minutes to complete the survey in each of the four lessons in which the questionnaire was administered. This gave students adequate time to complete the survey and allowed them to process their thoughts and provide more intentional responses.

Results

As previously established, multiple factors influence student motivation, from teacher pedagogy to social demographics of the classroom (Seifert, 2004; Yilmaz, Şahin & Turgut, 2017). This makes assessing and addressing student motivation with fidelity particularly difficult. Results from this intervention demonstrate those complexities of positively affecting student motivation in the classroom. The relationship between verbal affirmations of high expectations and student motivation varied across the two weeks for multiple reasons, many of which exist outside the scope of the research. Regardless, the results can be documented in two sections: Qualitative Results and Quantitative Results. A third section, Tertiary Results, details the relationship found between student motivation and academic performance.

Quantitative Results

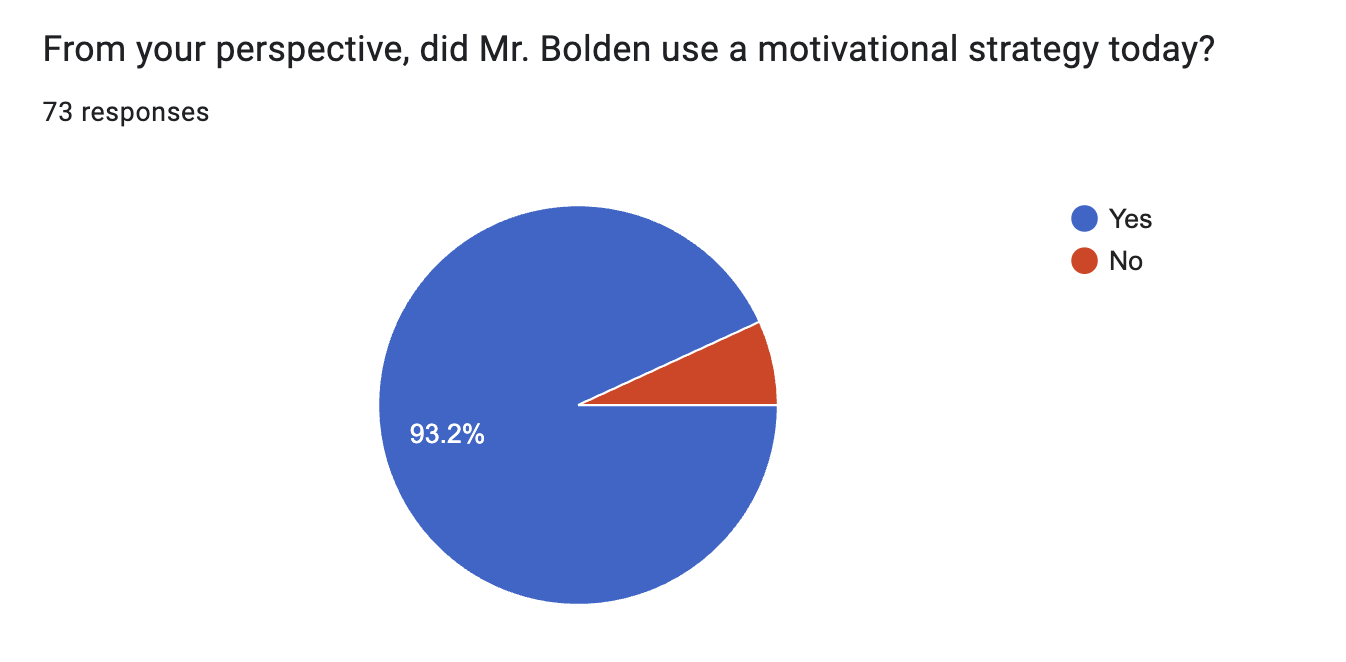

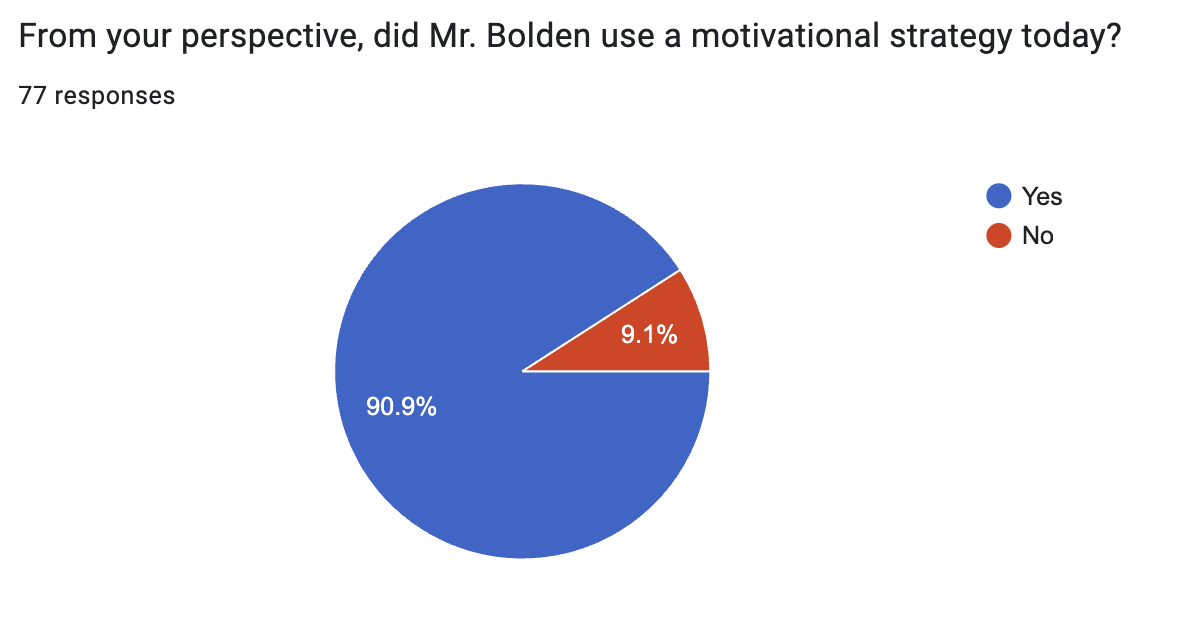

An identical questionnaire was provided to students during both weeks of the intervention, despite two different types of verbal affirmations being administered. There were 73 responses collected in week one, and 77 responses collected in week two. Response numbers vary based on student attendance data between weeks.

Figure 1: Pie chart showing student motivation ratings from the first week of intervention.

In response to the question, “On a scale from 1-5, how motivated were you throughout today's USH lesson?” the average rating in week one was 4.027 (see Figure 1). In week two, the average motivation made an insignificant drop to 3.974 (see Figure 2). The distribution of

responses were strikingly similar between weeks as evidenced in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 2: Pie chart showing student motivation ratings from the second week of intervention.

In response to the question, “From your perspective, did Mr. Bolden use a motivational strategy today?” 93.2% (68/73) of students responded “Yes” in week one (see Figure 3). The percentage of students who responded “Yes” dropped to 90.9% (70/77) in week two (see Figure 4).

Figure 3: Pie chart showing the percentage of student responses that indicated perceiving a motivational strategy in-class during the first intervention week.

This data indicates that most students perceived the teacher to use a motivational strategy throughout the lesson, but cannot specify which action they perceived as the motivational strategy. The qualitative data will provide more insight into whether or not students perceived the verbal affirmation, or another strategy, as the primary motivational strategy.

Figure 4: Pie chart showing the percentage of student responses that indicated perceiving a motivational strategy in-class during the second intervention week.

Qualitative Results

The qualitative data gathered from the same questionnaire was elicited via questions designed to provide context to student’s quantitative entries. Direct, per-student alignment of quantitative responses and qualitative context is not possible due to the anonymity of the questionnaire. However, the qualitative data contributes information about how students perceived the intervention and what other strategies consistently motivate them.

In response to the first follow-up question, “Explain your rating. What contributed to your motivation (or lack of motivation) today?” similar trends emerged from both weeks. The three main trends that students named as affecting their motivation (either positively or negatively) were: (1) intrinsic interest in the historical topic of the day, (2) instructional/classroom management strategies, and (3) quality home practices (quality sleep, praying at night/in morning, good interactions with family members) or the lack thereof. Student motivation was improved by interest in the topic and seemingly worsened if the student did not have genuine interest. For example, one student from week one responded with, “I have no motivation to learn about today's lesson but it's interesting so i don't mind,” which is an example of interest having a positive effect on student motivation. On the contrary, another student from week one reported that, “I have motivation, i just don't find any interest in the class.” Despite opposing dispositions to the content, the underlying message from these two responses is clear: academic interest has a positive correlation with student motivation.

In response to the second follow-up question, “Explain your last answer. What does Mr. Bolden do (or not do) to motivate students?” similar trends emerged between weeks again. Because there was content overlap between qualitative questions, similar themes from the first qualitative question were correctly anticipated. First, only 15.1% (11/73) responses in week one explicitly mentioned the verbal affirmations of high expectations, compared to 28.6% (22/77) of responses during week two. This comparison provides crucial context to the qualitative data from Question #2 by demonstrating that students were more likely to perceive the verbal affirmations as a motivational strategy when the students were directly involved in the activity (as opposed to being passive recipients of the affirmations in week one).

Other instructional strategies that students consistently named as motivational included providing multiple explanations/clarifications when students are confused (in both an individual and group context) and the use of background music to promote focus. Take these two student entries from week two of intervention as an example: (1) “Your a great help and theirs times im very confused and you explaining the work in examples makes your class more easier,” and (2) “Mr Bolden will if someone is struggling with one question then he will explain it to the whole class.” Regardless if it is whole-class or one-on-one, providing examples and clarifications for students can help students feel motivated in class.

The last qualitative question was optional, and it asked, “What could Mr. Bolden do better to motivate students in his class?”. While no major trends existed for this question within or between weeks, two repeated answers occurred back to back. Two students wished for a “better” soundtrack playlist (counter the jazz playlist I play every day during independent practice) and for me to crack a few more jokes to lighten the mood as we trudge through rather dense primary sources.

Tertiary Results

A positive correlation between student motivation and academic performance has been demonstrated consistently in recent decades (Lumsden, 1994; Bernaus & Gardner, 2008). To analyze the relationship between student motivation and academic performance in this specific context, student motivation ratings from the questionnaire were compared with successful assignment turn in percentage per intervention week (successful assignment turn in means a fully completed assignment earning a D- or higher). During week one of the intervention, 69.6% (39/56) of students successfully submitted both classworks, compared to 91.1% (51/56) successfully submitting both classworks in week two. There is a clear difference in successful submission rates, as students found more success in week two than they did in week one. These findings do not directly align with the student motivation data, nor the initial hypothesis. There are multiple factors that could be influencing the tertiary results, including differing attendance rates student experiences in and outside of the classroom. These potential confounding factors and other influences will be discussed in the discussion section.

Discussion

Because student motivation is affected by multiple variables outside of the teacher’s control, there are inherent limitations to what action research can “prove” about the effects of teacher interventions on their pupils’ motivation. Therefore, the results from this study can and should be interpreted from multiple perspectives, allowing educators to use what could work in their context and leave what may not. The goal of this discussion is to spark inspiration and conversation about what classroom initiatives, tools and strategies can be used to improve student motivation across variable contexts. Implications are based on the immediate context of the research.

Interpretations

The quantitative results demonstrate little difference between the effectiveness of teacher-led verbal affirmations of high expectations and teacher-student verbal affirmations of high expectations. Students audibly groaned on the second day of teacher-student verbal affirmations, indicating that they were annoyed with having to repeat my affirmation. A potential cause of their disposition is the idea that “repeat after me” style games are for elementary kids and not mature enough for teenagers. Still, their average rating of four out of five total points across both weeks indicates that students generally felt motivated in class. Students who were in class were typically able to complete their assignments on time, with most incompletions being a result of lack of attendance. This finding suggests that the student motivation crisis is a battle that must be overcome both in and outside of the classroom.

The qualitative results demonstrate that multiple students acknowledged verbal affirmations of high expectations (teacher-led and teacher-student) as a motivational strategy, but it is seen as a less effective motivator than intrinsic interest, instructional and classroom management strategies, and quality home practices. These results align with literature which suggests that student motivation is impacted by numerous factors, including classroom management and home environment (Seifert, 2004; Yilmaz et. al., 2017). Previous research also focused on improving student motivation through content-specific instructional strategies (Bernaus & Gardner, 2008). This too is aligned with the qualitative results as students cited feeling more motivated when their teacher was able to successfully support their comprehension of their class material.

Limitations

The most severe limitations exist within the design and implementation of the questionnaire. First, the anonymity of the questionnaire made it difficult to finely analyze the qualitative data by class or student, which could have shed light on more specific trends. Secondly, the wording of question number four (“Explain your last answer. What does Mr. Bolden do (or not do) to motivate students”) prompted students to give a general answer about strategies they can recall happening consistently, as opposed to which strategies I performed on the day of implementation. A more specific wording (What did Mr. Bolden do today to motivate you or other students?) would presumably elicit more qualitative responses naming the specific verbal affirmations as a motivational strategy used in class.

Finally, students did not respond well to having to take the questionnaire multiple times a week. By the second week, students were audibly complaining about the repetitive nature of the task. Their disdain for the questionnaire is evidenced by an increase in ambivalent or repeated answers in week two. Although there were genuine student responses documented, the query exists whether or not the questionnaire was valid or if student responses were affected by their general disposition. While anonymity is still a strong tool to promote validity, it can not fully prevent student burnout. Future research should consider administering questionnaires no more than once a week to prevent this limitation.

Implications

This research demonstrates the need for sound instructional strategies, lesson preparation, and classroom management skills in order to foster student motivation in the classroom. Teachers can not control their students' sleep habits, but we can work to ensure that students benefit from an educational environment where even the most fatigued student is set up for success. This includes the opportunity for students to work in a calm classroom, develop self-efficacy, and to receive proper scaffolding when stuck; all of which develops gradually for teachers by strengthening one’s pedagogy through consistent reflection and thorough preparation.

For practitioners who are attempting to assess and analyze student motivation, this study demonstrates the benefits of using a mixed methods approach that allows for qualitative student input. Students are the primary stakeholders of our education system and their voices should be heard, mostly because they have the most critical insight to offer. While their responses may not always be practical for the classroom setting, one of the best ways to figure out what motivates students is by asking them directly.

Conclusion

Although the two types of verbal affirmations did not yield a significant difference in student motivation levels, the qualitative data gathered from the study provides nuanced perspectives into what factors contribute to, or take away from student motivation. Student motivation in my US History context has been most consistently affected by student interest in the historical topic, instructional and classroom management strategies used during the lessons, and the presence of quality home practices. However, these findings are not exhaustive and may differ between contexts and demographics. Further research should be conducted to better understand (a) the factors that affect student motivation in varying contexts, and (b) the relationship between student motivation and teacher pedagogy.

References

Bernaus, M., & Gardner, R. C. (2008). (PDF) teacher motivation strategies, student perceptions, student motivation, and English achievement. The Modern Language Journal. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227634425_Teacher_Motivation_Strategies_Student_Perceptions_Student_Motivation_and_English_Achievement

Lumsden, L. S. (1994, May 31). Student Motivation To Learn. ERIC Digest, Number 92. ERIC. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED370200

McMillan, J. H., & Hearn, J. (2008). Student self-assessment: The key to stronger ... educational HORIZONS. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ815370.pdf

Seifert, T. (2004). Understanding student motivation. Educational Research, 46(2), 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013188042000222421

Sibieta, L., Greaves, E., & Sianesi, B. (2014, September 30). Increasing pupil motivation: Evaluation report and executive summary. Education Endowment Foundation. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED581249

Yilmaz, E., Şahin, M., & Turgut, M. (2017). Variables affecting student motivation based on academic ... Journal of Education and Practice. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1140621.pdf